For class on October 8th, find 5 historical news articles on the Windscale disaster from the 1950s-1970s in the historical London Times database available through Galvin Library. Compare these articles with what we now know about Windscale–both the disaster and the nuclear plant’s reasons for existing at all.

In a short essay (no more than 600 words), talk about the speed at which information was (and wasn’t) available to the public. Explain what a reasonably informed member of the British public at the time would have known and thought about Windscale, and the safety of nuclear power, on the basis of the articles you find. Support your points with specific examples from your articles.

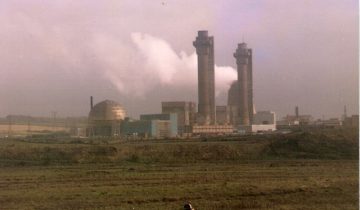

The near disaster at Windscale is another classic example of how political the interests of the few in authority are put before the best interests of the public. The events that had transpired throughout the Cold War had the leaders of the United Kingdom convinced that a nuclear alliance with the United States would re-establish the country as a world power and was necessary at all costs. The nearing deadline for delivering the bomb pushed the already stressed nuclear facility to and beyond its limited capacity. As the scientists of the jeopardized nuclear plant voiced their concerns of the impending dangers of exceeding the plant’s capacity, on October 8th 1957 these concerns were about to materialize during a routine Wigner energy release.

The Saturday following the incident, The Times published a synopsis of the situation and series of statements made by the UK’s Atomic Energy Authority (AEA) that suppressed the gravity of the fire. Sir Leonard Owen managing director of the AEA flew in from headquarters and was “satisfied that the situation was well under control. At no time was there any risk of an explosion. With exception of the reactors themselves the whole of the Windscale plant area has now returned to normal operation” (1). The statement continued: “The combustion is now being held. The staff are now injecting water on it from above and the temperature has started to fall. There is no evidence of there being any hazard to the public. This type of accident could only occur in an air cooled circuit pile and could not occur at Calder Hall or any of the power stations now under construction for the electricity authority” (1). These statements were made to preserve public opinion of the authority’s execution and regulation of safe nuclear operations, but to also protect the reputation of the nuclear gem Calder Hall.

During an annex of documentation of the incident, the Prime Minister released a report in regard to the second Wigner release where chairman of the AEA Sir Edwin Plowden states that “the immediate cause of the accident was the application too soon and at a too rapid a rate of a second nuclear heating to release to Wigner energy for the graphite of the pile, thus causing the failure of one or more cartridges, whose contents then oxidized slowly, eventually leading to fire in the reactors.”(3) He continues by stating that “the authority having considered the findings of the committee of inquiry had come to the conclusion that the cause lay partly in faults of judgment by the operating staff. These faults were themselves attributable to weakness in the organization”. (3)

Clearly the circumstances that led to the incident where not clearly identified nor where they stemmed from. Accountability, or lack thereof, was shifted in the wrong direction. Statements released by the secretary of the Institution of Professional Civil Servants depict how the scientists were “seeking the rehabilitation of their professional reputation.”(4) and “they feel that the authority has used them as a scape goat” (4). They were “condemned by public opinion by the one accident which had been free from any serious permanent disaster”. (5)

These scientist were mere chefs given a recipe for disaster for a nuclear hungry Prime Minister. Authorities were elusive in reassuring the public that everything possible had been done to avoid such an incident and on the possibility of a repetition of the accident. The AEA reiterated over and over that this was not possible. Very typical of large governing bodies, information was distorted to keep the public at peace.

1) Windscale Atom Plant Overheats. From Our Special Correspondent. The Times (London, England), Saturday, Oct 12, 1957; pg. 6; Issue 53970.

2) Second Pile At Windscale Closed Down. From Our Special Correspondent. The Times (London, England), Friday, Oct 18, 1957; pg. 10; Issue 53975.

3) Causes Of Windscale Mishap. From Our Science Correspondent. The Times (London, England), Saturday, Nov 09, 1957; pg. 4; Issue 53994.

4) Windscale Staff To Be Heard. The Times (London, England), Tuesday, Jan 14, 1958; pg. 8; Issue 54048.

5) Lessons From Windscale. The Times (London, England), Friday, Nov 22, 1957; pg. 3; Issue 54005.

The Windscale Disaster

Following the Windscale Disaster, which took place on October 10, 1957, surprisingly little information was available to the public as to the cause of the fire (which ranked a 5 on the 7 point International Nuclear Event scale – a serious nuclear incident). In the days immediately following the fire, very little information was released to the public about the accident, other than the general assurances that nobody was hurt, and nobody was at risk in terms of radiation leakage.

Citizens of the United Kingdom was provided with very vague statements from the press and the management of the Windscale plant, with releases such as “‘At this stage it is not possible to give the cause for the accident. It is likely that the pile will be out of operation for a period of some months,’” which was printed in the October 12, 1957 release of the London Times. In the same paper, headlines such as “Men Sent Home” and “Out of Operation” give very little details about the happenings of the fire. The article also notes that an official statement was delayed because “their immediate concern was naturally to cope with the incident itself.” Interestingly enough, the article also briefly notes the true mission of the Windscale plant, the creation of Plutonium for atomic bombs, but no sense of urgency or concern is evident by the release. In an article published a few days later, on October 19, 1957, a press release by Mr. H. C. Davey, the Windscale general works manager, is noted as “dismissing categorically the possible dangers to health from virtually every source other than the intake of milk by young children.” It is also noted that “this was accepted by everyone.”

These articles show that the population of Cumberland and, by extension, the UK, believed indubitably in the ability of the Windscale crew to handle the situation. The media during the days following the Windscale disaster, which, again, was a major nuclear disaster, seems oddly content with the vague statements given by the Windscale crew and raises very few questions about why a disaster of this caliber occurred, and what the true purpose of the Windscale plant is – because this disaster should not have occurred in the first place if the production of Plutonium had not been stressed so heavily.

Finally, in an October 22, 1957 publication of the London Times, the first indication of action being taken to prevent any further damage to Windscale is seen, and the Times reports that “today the Windscale general works manager, Mr. H. G. Davey, was recalled before Sir William Penney’s committee. There is a possibility that the [inquiry’s] end may be reached tomorrow.”

These reports cover up to twelve days from the day of the accident, yet the media shows absolutely no concern or outcry toward the severity of the Windscale disaster. In more contemporary times, if a nuclear reactor were to catch fire as did Windscale, media outrage, especially from more conservative media precincts, would be severe. The disaster and subsequent outcry would put a black eye on nuclear energy as a viable alternative energy source and would prompt massive debate and fear over the topic, much like the media treats the recent Ebola outbreak. Yet, interestingly enough, this sort of outcry isn’t evident in the London Times articles from around the time of the disaster. The media appears to be content with the information provided by the Windscale crew, which conveniently neglects to mention the reason for the fire – stress put on the piles because of shortcuts taken by the crew to increase the Plutonium output to provide more Plutonium for the government, which was demanding larger and larger amounts to feed their bomb projects.

As public emotions usually follow the media in intensity, it is likely that the average citizen of Cumberland felt relatively safe following the statements by the Windscale crew, which were reported in the London Times, if not slightly uncomfortable and/or scared in the day or so following the accident before any press releases were made assuring their safety. Considering that Windscale was largely operational in the years following the accident, it is likely that public opinion of nuclear energy was not changed a significant amount, and most still considered it a reasonable alternative energy source.

Sources:

Our Special Correspondent. “Windscale Atom Plant Overheats.” Times [London, England] 12 Oct. 1957: 6. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=TTDA&userGroupName=chic7029&tabID=T003&docPage=article&searchType=&docId=CS100882764&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

Our Special Correspondent. “Manager Describes Events At Windscale.” Times [London, England] 19 Oct. 1957: 6. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=TTDA&userGroupName=chic7029&tabID=T003&docPage=article&searchType=&docId=CS102848851&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT. “Windscale Inquiry Nearing End.” Times [London, England] 22 Oct. 1957: 2. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=TTDA&userGroupName=chic7029&tabID=T003&docPage=article&searchType=&docId=CS33904982&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT. “Radioactivity Effect On Dairy Cattle.” Times [London, England] 2 Sept. 1959: 7. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=TTDA&userGroupName=chic7029&tabID=T003&docPage=article&searchType=&docId=CS119233826&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

“Radiation Check After Error At Windscale.” Times [London, England] 20 Nov. 1963: 10. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=TTDA&userGroupName=chic7029&tabID=T003&docPage=article&searchType=&docId=CS169043316&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0

After the Second World War, the British government decided to embark in nuclear weapons. That led to the creation of the Windscale nuclear plant. However, on October 10th, 1957, one of the nuclear reactors in Windscale set fire. It was determined by the government initially that it was the fault of the workers, but that may not be the case. One thing that became clear after the Windscale disaster was that it was not just a technical issue, but an issue of overall design and handling as well.

There is the idea that the development of these reactors at Windscale was too fast. While the reactors were successful in their job of creating Plutonium, they were inefficiently built. The reactors would not be a lasting product due to the atmospheric air as the way to cool the reactors. As suggested, it could be said that “These reactors are still effective producers of plutonium but they are completely out of data and they will stand there in a hundred years’ time not in use, but as a monument to our initial ignorance” (Warning on Development of Nuclear Energy) This idea goes into effect when considering what people learned about the cause of the reactor.

After the fire, there was a secret hearing on what had happened, most likely to keep information on the amount of plutonium secret. (Only Frankness can Reassure.) Due to that, the information released to the public about what had happened was only a part of the information. The public learned that it was caused by a second Wigner release, which was normally a standard procedure. However, while that was the primary cause, the cause goes much deeper.

The public would then learn about the organizational shortcomings of Windscale. As stated, “led the staff of the Authority, and in particular the industrial Group, to accept collectively and individually a programme of work which has kept them continually under severe strain.” (Too Few at the Top.) This could be said as the primary reason for the issues at Windscale, as the expectations were set too high.

The people of Britain would be quite apprehensive about nuclear power directly after the disaster. However, as more information became available about it, it would become clear that it was due to bad managing of the project that the disaster happened. That said, assuming that future dealings with nuclear power is on a much longer timeline with less stress put on the designers of it, I would say there would be an eventual accepting of nuclear power.

Sources Used:

Only Frankness Can Reassure.

The Times (London, England), Wednesday, Oct 16, 1957; pg. 11; Issue 53973.

Errors Admitted.

The Times (London, England), Saturday, Nov 09, 1957; pg. 7; Issue 53994.

Too Few at the Top.

The Times (London, England), Friday, Dec 20, 1957; pg. 11; Issue 54029.

Warning On Development Of Nuclear Energy.

The Times (London, England), Tuesday, Sep 20, 1955; pg. 4; Issue 53330.

Causes Of Windscale Mishap.

From Our Science Correspondent.

The Times (London, England), Saturday, Nov 09, 1957; pg. 4; Issue 53994.

Limited information was released to the public of Britain as well as the consequences of the Windscale disaster. Although there was relatively little information provided, this information was not much useful for the Sellafield residents in order to take cautious measures. This lack of information demonstrates the intentional risks that are often made by government.

The Windscale incident illustrates the extent to which government races in order to achieve their political goals; such that this was Britain’s strategy for running in the ‘Atom Race’. Britain was under the pressure of the cold war and wanted to develop a powerful atomic bomb to practice its political power through deterrence. In addition to the pressures from the race, the Windscale reactor was under budget constraints and this caused the project to rush the process, leaving cautious mechanisms behind.

There were also disputes between different agencies and authorities. The article, Medical Officers Disagree from November 1957, summarized the lack of communication and of trust that authorities had on each other for fear of releasing information to the wrong hands. In this article the United Kingdom energy authorities and public health authorities were arguing the atom energy authority made no attempt in alarming the public health authority of the consequences that this accident had because their lack of confidence.

Articles demonstrated the limited knowledge that the public received from the media, but no accurate or thorough information was provided to inform the public of the risks that this accident had on their health. In an article from October 1956, The Guarantee of Safety Protection Built IN, informed the public of the preventive procedures that they were following for the workers from the nuclear power station. However, this article illustrates how the authorities and councils tried to keep this disaster under silence by conveying the public that there was no impact to their health. “These are comforting words; there is no reason to believe that the realization of our hopes for prosperity in the new era of nuclear power will be delayed in any way by the associated problems of health and safety”, this is one of the quotes from the Medical Research Council in this article demonstrated their camouflage the real health effects.

The only people who were completely knowledgeable of the risks to the nation, were those who were leading the project. Government officials recognized what were the potential risks that this nuclear reactor would cause to the public health, if something went wrong, but there was no slowing down. In Health Aspects of Windscale from The London Times demonstrated the values and priorities of the reactor leaders and government, since the Lord of the President Council was asked if there were considerations of the public health and their anxiety over this accident and his response was that they did but that the reputation of the researchers was of priority.

In conclusion, the general public was un-informed off what was really happening and what this accident meant to their health and that of their families. It is obvious that much information was running through the hands of those in powers or more to say the leaders of the reactor. The general public, specifically those with low to no knowledge of radioactivity, would have been able to realize the critical effects that this accident had to offer to the region. Those individual institutions with authority attempted to hide the serious consequences and avoid the panic in the public, which was visible through their attitudes in the news articles.

.

Atom Fuel Workers to Get Health Checks. (1975, January 30). The Times(Lond, England), p. 3.

Choate, R. (1976, November 17). Nuclear Renege pleases Industry. The Times(London, England), p.21.

Health Aspects of Windscale. (1957, October 30). The times(London, England), p. 4.

Medical Officers Disagree. (1957, November 08). The Times(London, England), p. 15.

The Guarantee of Safety. (1956, October 17). The Times(London, England), p. x.

October 12th, 1957

[Charles coming back from his morning promenade]

“After all, it’s Saturday. What can they possibly be doing? I should question my wife since she stayed at home all day yesterday with the children. But this unusual activity is odd indeed. Cumberland is a peaceful county on weekends, besides of course for this plant… There’s is always something going on!”

[Getting today’s newspaper]

“Dear Lord! Windscale had a accident Theresa! I knew it! Like I said there is always something going on over there and these idiots at Windscale finally pushed the wrong button. I’m glad Theresa had the boy bring the paper over, otherwise we would never knew a word about it.”

[Reading]

“They are saying that no one was hurt in any way and that there was no explosion, but why would they want workers in the vicinity to keep under cover (Our Special Correspondent)? This doesn’t make sense at all. Of course there is no danger since there was no explosion! These scientists always want to complicate things.

Theresa, was kind of “military purpose” would need plutonium do you think? Well yes, I’m telling you what the reporters are telling us. However my dear, I honestly don’t understand where all the fuss is coming from, because they are saying everything is well under control, are they not?”

October 28th, 1957

“Theresa! It’s official now! We can have them send the milk again. Let’s pray that they didn’t have to go out of business… Good Lord, who knows how many gallons these poor farmers dumped away! Not even three weeks and this has been too painful to watch.

I’m telling you, scientists want to waste our money on every occasion! They are now launching investigations to find out the causes of the accident. When will they understand that we will just get burned whenever we play with fire?

By the way, Theresa, why are they putting someone from the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at the head of the committee for investigations?” (Our Correspondent)

More than a comfortable 30 years after the accident, it is now public that United Kingdom’s prime minister “Harold Mcmillan […] personally censored an inquiry report on the ground that it would jeopardize efforts to persuade the Americans to share their nuclear secrets with Britain” (David Walker). In other words, the people from Cumberland and the whole England were not told the real story of what was behind the plutonium factory and the reason why they were pushing for the production to go faster; and the information was held from them by the Government to prevent the United States from thinking the UK was not worthy to be a good nuclear partner because they couldn’t even handle a small atomic plant correctly.

In 2007, The Times was doing mention of a film about the disaster at Windscale. The contrast then was very obvious in the details divulgated: Not only the article openly referenced the link between Windscale and Britain’s nuclear treaty with the US, but it is clear that the scientists had no idea what to do nor what would be the end result from the moment the “graphite core of the nuclear reactor caught fire” (David Chater).

Possibly the best reference to illustrate the state of mind with which the authorities were ready to fly over the Windscale disaster with the least possible seriousness is the following small section describing the event of october 10th 1957; the passage reads:

“Oct 10: A nuclear reactor became overheated at Windscale plutonium factory. No casualties.” (The Year)

Works Cited

Our Special Correspondent. “Windscale Atom Plant Overheats.” Times [London, England] 12 Oct. 1957: 6. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 5 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/newspaperRetrieve.do?sgHitCountType=None&sort=DateAscend&tabID=T003&prodId=TTDA&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchId=R1&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm¤tPosition=3&qrySerId=Locale%28en%2C%2C%29%3AFQE%3D%28tx%2CNone%2C9%29windscale%3AAnd%3AFQE%3D%28tx%2CNone%2C8%29accident%3AAnd%3ALQE%3D%28da%2CNone%2C4%291957%24&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&userGroupName=chic7029&inPS=true&contentSet=LTO&&docId=&docLevel=FASCIMILE&workId=&relevancePageBatch=CS100882764&contentSet=UDVIN&callistoContentSet=UDVIN&docPage=article&hilite=y

Our Correspondent. “Windscale Milk Ban Eased.” Times [London, England] 29 Oct. 1957: 10. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 4 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/newspaperRetrieve.do?scale=0.33&sort=DateAscend&docLevel=FASCIMILE&prodId=TTDA&tabID=T003&searchId=R1&resultListType=RESULT_LIST¤tPosition=13&qrySerId=Locale%28en%2C%2C%29%3AFQE%3D%28tx%2CNone%2C9%29windscale%3AAnd%3AFQE%3D%28tx%2CNone%2C4%29milk%3AAnd%3ALQE%3D%28da%2CNone%2C8%2910%2F%2F1957%24&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&fromPage=&inPS=true&userGroupName=chic7029&pageNumber=&docId=CS169564509¤tPosition=13&workId=&relevancePageBatch=CS169564509&contentSet=LTO&callistoContentSet=UDVIN&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&reformatPage=N&docPage=article&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&dp=&searchTypeName=AdvancedSearchForm&newScale=0.50&docPage=article&enlarge=&recNum=&newOrientation=0&navigation=true&pageIndex=1&searchTypeName=AdvancedSearchForm

David Walker, Public Administration Correspondent. “MacMillan ordered Windscale censorship.” Times [London, England] 1 Jan. 1988: 4. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 5 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/newspaperRetrieve.do?sgHitCountType=None&sort=DateAscend&tabID=T003&prodId=TTDA&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchId=R1&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm¤tPosition=2&qrySerId=Locale%28en%2C%2C%29%3AFQE%3D%28ti%2CNone%2C18%29windscale+disaster%3AAnd%3ALQE%3D%28da%2CNone%2C10%29%3E+07%2F%2F1957%24&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&userGroupName=chic7029&inPS=true&contentSet=LTO&&docId=&docLevel=FASCIMILE&workId=&relevancePageBatch=IF501735196&contentSet=TDA&callistoContentSet=TDA&docPage=article&hilite=y

David Chater. “Windscale: Britain’s Biggest Nuclear Disaster.” Times [London, England] 8 Oct. 2007: 19[S]. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 5 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/newspaperRetrieve.do?sgHitCountType=None&sort=DateAscend&tabID=T003&prodId=TTDA&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchId=R1&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm¤tPosition=3&qrySerId=Locale%28en%2C%2C%29%3AFQE%3D%28ti%2CNone%2C18%29windscale+disaster%3AAnd%3ALQE%3D%28da%2CNone%2C10%29%3E+07%2F%2F1957%24&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&userGroupName=chic7029&inPS=true&contentSet=LTO&&docId=&docLevel=FASCIMILE&workId=&relevancePageBatch=IF503728113&contentSet=TDA&callistoContentSet=TDA&docPage=article&hilite=y

“The Year In Retrospect.” Times [London, England] 1 Jan. 1958: 12. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 4 Oct. 2014.

http://find.galegroup.com.ezproxy.gl.iit.edu/ttda/newspaperRetrieve.do?scale=0.33&sort=DateAscend&docLevel=FASCIMILE&prodId=TTDA&tabID=T003&searchId=R1&resultListType=RESULT_LIST¤tPosition=3&qrySerId=Locale%28en%2C%2C%29%3AFQE%3D%28tx%2CNone%2C10%29windscale+%3AAnd%3AFQE%3D%28tx%2CNone%2C8%29disaster%3AAnd%3ALQE%3D%28da%2CNone%2C11%291957+-+1960%24&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&fromPage=&inPS=true&userGroupName=chic7029&pageNumber=&docId=CS201546273¤tPosition=3&workId=&relevancePageBatch=CS201546273&contentSet=LTO&callistoContentSet=UDVIN&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&reformatPage=N&docPage=article&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&dp=&searchTypeName=AdvancedSearchForm&newScale=0.50&docPage=article&enlarge=&recNum=&newOrientation=0&navigation=true&pageIndex=1&searchTypeName=AdvancedSearchForm

The safety of nuclear technology is an issue as much today as it was during the Windscale pile fire. News reports have a tendency to downplay disasters of this magnitude, or they lack sufficient evidence to truly depict the overall safety after such an event.

Articles ranging from the fifties on through the seventies all have a vague sense of the problems that occurred at Windscale, the true cause of the accidents, and how safe the surrounding land is afterward. From the perspective of someone reading their daily paper in 1958, it would be incredibly hard to gain enough understanding to come to a judgment backed by evidence. While the government admitted that radioactive elements were indeed released from Windscale they state that the level of radiation remains safe within one-hundredth to one-fifth the level that a person can live without negative effects during their lifetime (Inquiry Ordered at Windscale). Milk was gathered and disposed of by government officials following the incident, but the government assured the public that this was merely an over-precaution to make sure that no ill effects could possibly occur. The article Atomic Danger “Uneasiness”, published in The Times in 1958, even goes so far as to call up statistics relating to the coal and natural gas sector’s safety.

The normal person in England during this period was quite likely ill at ease with the nuclear plants, but at the same time they probably didn’t know just how dangerous they were. Farmers speaking to the Atomic board seemed concerned with the short to mid-term issues relating to their crops and livestock, while they didn’t seem to voice concern over their own well-being. Since a nuclear disaster had never occurred prior to this and the effects of radiation on the body were not yet sufficiently researched, the general consensus seemed to be that conditions were safe. The papers refer to boards of the highest authority, but don’t lend any facts to back the numbers they provide. Readers may have thought, what is considered a safe amount of radiation within a lifetime?

In cases like Windscale, which set a precedent for man-made disasters, it is difficult for journalists to give any clear answers on what occurred or the conditions that result from the event. Looking back from our perspective in history we may say well of course that’s unsafe! How would your typical person come to that conclusion in say, 1960? For that matter how could members of the atomic board know things related to the operation of Windscale when they were located in Calder Hall (or further still in London). The voices of engineers with some know how relating to the fire (or the other issues relating to Windscale over time) seem oddly quiet in this sense. It may be that none of the engineers spoke up, but what seems more likely is their credibility on the topic was overlooked when it was being reported on.

Nuclear facilities are certainly not safe playgrounds to joyfully prance through, but just how dangerous are they? Even today that question lingers. Plants like Dresden and Braidwood (two nuclear plants right here in Illinois) have been leaking tritium and diesel into drinking water for years, they are past their original planned operation lifetime, and draw on them is higher now than ever before. Are we any more informed about our risks than those living near Windscale had been? When was the last time you picked up a newspaper and saw an article that informed people of the risks of the nukes right in our backyard?

Bibliography

Atomic Danger “Uneasiness”. (1958, October 7). The Times.

Farmers Given Assurance On Reactor Effects. (1957, October 23). The Times.

Inquiry Ordered At Windscale. (1957, October 16). The Times.

Uneasiness at Calder Hall. (1957, October 17). The Times.

Wright, P. (1970, September 22). Cause of Incident at Windscale Atomic Plant Still Uncertain. The Times.

The sources for news in the 1950’s were more limited than they are today with the general public of this generation having access to the internet. An average citizen in the 1950’s had access to radio, newspaper, and only limited TV access. Because this is true, a person living in this time may not have received the news of this disaster until days after its occurrence. The Windscale Disaster took place on Oct. 10, 1957, but the first article about the disaster was posted on Oct. 12, 1957. Even then the news did not give the entire story or all the facts. The first article posted on Oct. 12 stated: “Some oxidization of uranium has occurred. The greater part of this has been retained by the filters in the Windscale chimneys. A small amount has been distributed over the works site, and in some areas works personnel have, as a precaution, been instructed to remain under cover.” Clearly not all the information was being given about the disaster especially the important part of what areas were affected. The article gives an overview of the events, but never goes into greater detail. An average citizen reading this newspaper would have no idea if the disaster affected 1 sq mile or 1,000 sq miles.

Although early on information involving the cause of the fire was hazy (said to be a misjudgment by the operators), later on the effects of the disaster were thoroughly documented. One of the major issues was that the milk around the surrounding area was supposedly contaminated. We know today that 500 sq km surrounding the plant had to dispose of any milk produced for over a month. An article titled Milk Ban over 200 sq. Miles was one of the first to report about the incident. It covered the facts such as why the milk was thought to be contaminated, who would be affected, how many people were affected, and even informed the public of the compensation the farmers would receive for their loss. All this information was posted the day after the police were asked to stop distribution of milk in the affected areas (October 15, 1957). The public was given the same amount of information in this article as somebody today could find out about the incident.

Finally on October 23, 1957 an article was posted which had all information regarding the disaster. The article was a Q&A style which involved surrounding farmers and the general public asking important questions regarding the incident. One quote which sums up the article states: “they told nearly 300 farmers that little more than an ounce or two of radioactive iodine has been deposited over an area of 200 square miles around Windscale; that there is no conceivable danger to livestock or from vegetables; and that Atomic Energy Authority and the Ministry of Agriculture were so anxious to reassure farmers that they have been taking samples of all farm produce as well as making blood tests on animals and taking samples from the thyroid glands of local cattle.” Simply put, the farmers were unaffected after extensive tests were done on the surrounding areas.

Information on the disaster had been given to the public in increments starting two days after the disaster had happened. The most useful article which would relieve any anxiety about the disaster’s magnitude was not received until two weeks prior to the accident on October 23rd. The public eventually was well informed, but not immediately like we would be today.

References:

“Milk Ban Over 200 Sq. Miles.” Times [London, England] 15 Oct. 1957: 10. The Times Digital Archive.

Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

Our Special Correspondent. “Windscale Atom Plant Overheats.” Times [London, England] 12 Oct. 1957:

6. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

Our Special Correspondent. “Farmers Given Assurance On Reactor Effects.” Times [London, England] 23

Oct. 1957: 6. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.